Before the mass began that evening, as my husband snapped photos of Daniel and his friends leaving flowers at the foot of Our Lady’s statue, I looked around at the young girls, little “brides”, bustling and beaming in their veils and white dresses. And I was reminded of a story my friend Kasia told me about her First Holy Communion in Poland, back in 1970.

In Poland, she said, the children received their First Communion at a special mass on Sunday, and then all that week, they would come to the evening mass at their parish and wear their white dresses and special clothes to make the whole week a celebration of that union with Christ. (What a beautiful practice, I thought, for in the ancient Jewish tradition a marriage was celebrated for a week – at the house of the bridegroom!)

Kasia smiled as she remembered rushing home after school, changing into her white dress, shaking the braids out of her hair, and donning her crown of flowers. Her friend Ania lived in the same communist-built apartment building, and together the two eight-year-olds would race down the streets of their town of Wloclawek to the Cathedral, over a mile away. Every day they arrived breathlessly at the five o’clock mass, excited but disheveled, their hair wind-blown and floral crowns slightly askew.

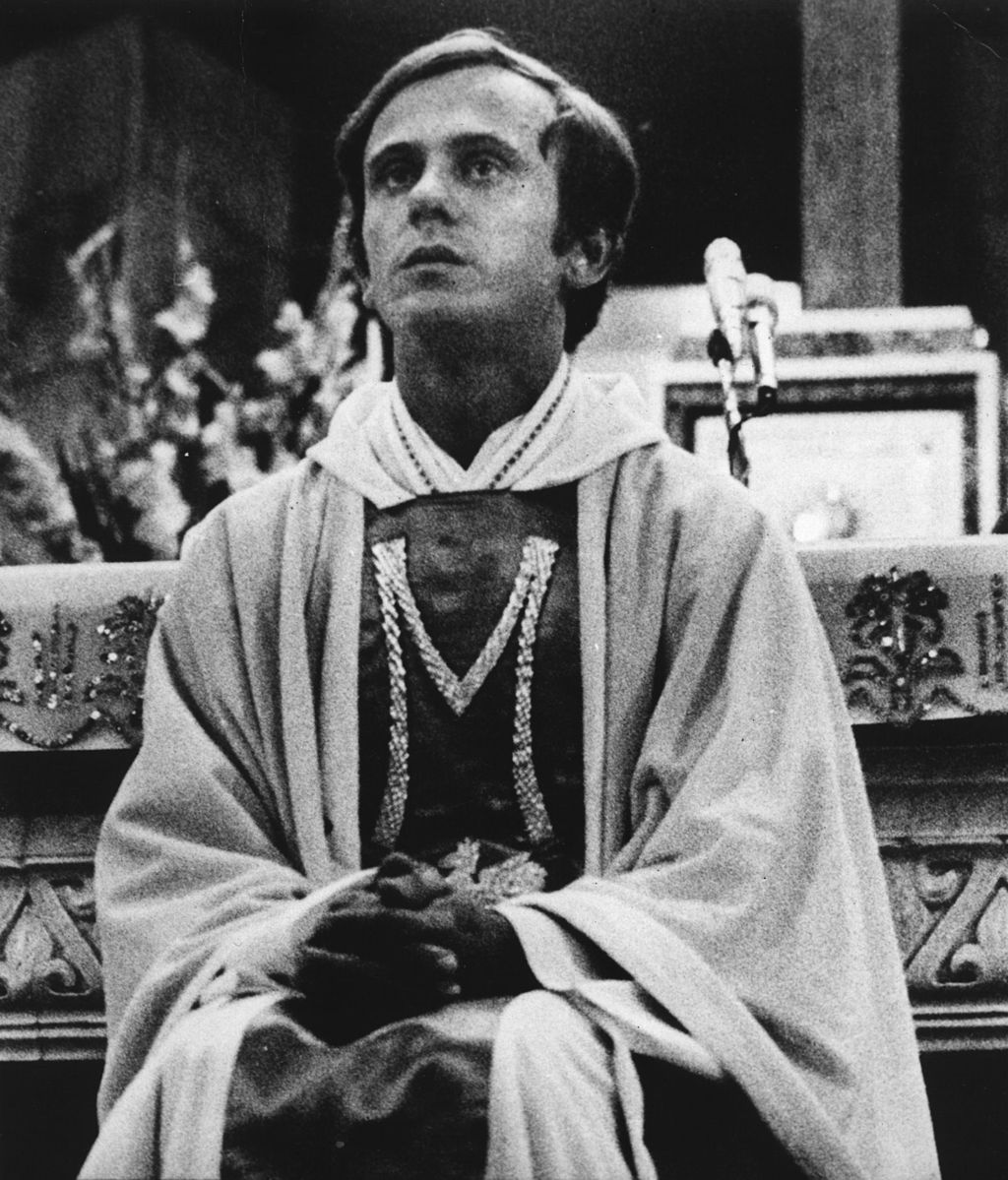

Oh no, she said. The Catholic faith and its traditions were so ingrained in the culture “they” didn’t dare openly stop it, she said. As she remembered, even the communists in her town were Catholic. And then I recalled reading, again in Witness of Hope, that when he was the archbishop of Krakow, Saint John Paul II would continue the annual Corpus Christ procession each spring, carrying the Eucharist through the city and preaching to tens of thousands of people in the streets. It wasn’t until the strikes began decades later, when, emboldened by their new Polish pope and then encouraged by many priests, the people began to be filled with optimism and hope. The government realized its efforts to make Catholicism nothing more that a sentimental fable had failed, and leaders began to fear the influence of the Church. In fact, Kasia recalled, eventually Wloclawek would have it’s own martyr: Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko. Fr. Popieluszko was a young priest, only 37 years old, when he was beaten to death by three Security Police officers after his anti-communist sermons, broadcast throughout Poland, became too much of a threat to the regime. His body was then thrown into the river near Wloclawek. Over 250,000 people boldly attended his funeral. (A miracle attributed to his intercession was confirmed in France in 2013 and it is expected that he will be canonized soon, as a martyr.)

We too in the Church now, must dress ourselves in the whiteness of the confessional (for we know the result of coming to the bridal banquet improperly attired – see Matthew 22!) and run, run to Christ, without looking left or right. As the culture throws itself into flames, and freedoms begin to falter, and the things we love turn to dust and so many others are turning to pillars of salt, we have to fix our eyes on the one sure thing, the center of our existence and race to Him. And then, we hope, we’ll make it someday to the wedding banquet, a bit tousled and winded, perhaps, but in the end – arriving absolutely awestruck and among the saints….several of my favorite being, in fact – Polish.

Only children, and those like them, will be admitted to the heavenly banquet.

~St. Therese of Lisieux

Claire Dwyer is an unapologetically Catholic mom to six beautiful kids ages 17 to 3 and lucky wife to a great – and very patient – man. She finds finds joy in the surprising little glimmers God gives us of Himself – unexpected suggestions of heaven in the everyday, even in the crumbs and chaos. She delights in the sacramentality of daily life; and in the discovery that everything points to something beyond itself. With that lens that we find in the deepest pockets of our prayer, we see the glimpses of clarity in the shadows. And sometimes, by grace, the sun startles us with its brilliance. Her blog at “Even the Sparrow” can be read here.